//

Perhaps the best comparison when looking back at the hundreds of cartoons printed in newspapers and magazines during the 1984-5 miners’ strike is that they were the equivalent of today’s postings on social media, often provocative, abusive, and sometimes downright cruel, intended to prompt comment and debate.

Perhaps the best comparison when looking back at the hundreds of cartoons printed in newspapers and magazines during the 1984-5 miners’ strike is that they were the equivalent of today’s postings on social media, often provocative, abusive, and sometimes downright cruel, intended to prompt comment and debate.

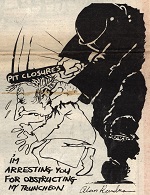

The miners’ struggle against pit closures divided the country. Cartoonists from right to left offered their take on an unfolding and unyielding polarisation between the state and the mining communities.

No cartoonist could have asked for more: a cast of larger-than-life characters in a fight to the death. There were plenty of opportunities to poke fun at the leading protagonists, but the overarching challenge was to keep pace with the anger and disarray that erupted during a dispute from which there seemed no way out.

Imagery around the violence generated by the strike was pushed to the extremes. Some cartoons depicted a country at war with itself.

Striking mineworkers were characterised as thugs, wearing hoods, wielding baseball bats; their leader Arthur Scargill a Communist stooge, branded with the hammer and sickle; police officers with truncheons constantly cracking down on the heads of peaceful pickets; and reigning supreme, often above the fray, Margaret Thatcher, in a Churchillian pose.

No single British industrial dispute has ever equalled the year-long pit strike for generating so many cartoons.

National, regional, and local newspapers were in their heyday in the early 1980s: ten national dailies were selling almost 15 million copies a day.

There was no rolling television news or the likes of Facebook and Twitter for the press to compete with.

Most nationals printed a daily cartoon, sometimes two or three a day. No colour printing then, just black and white, but the cartoons had great impact and leapt from the page.

Occasionally a cartoon caught the mood of the nation, having a greater effect than a press report or photograph.

Occasionally a cartoon caught the mood of the nation, having a greater effect than a press report or photograph.

Day after day the imagery on display tended to exaggerate the storylines in newspapers and on radio and television, reinforcing the widening divisions between the British establishment and the miners and their families.

As the violence intensified and the positions of both sides became more entrenched, the greater the manipulation of the political and news agenda.

Conservative-supporting newspapers demonised Scargill in his role as President of the National Union of Mineworkers, whereas Mrs Thatcher, hero of the hour, was the Prime Minister defending the rights of working miners, resolute in her determination to defeat the strike and end unlawful picketing at the pits.

Scargill was portrayed as the law breaker, a representation fleshed out to extraordinary lengths by Michael Cummings, cartoonist for the Daily and Sunday Express, who visualised the NUM President as a puppet of the Soviet Union, threatening Britain’s democratic institutions.

Scargill was portrayed as the law breaker, a representation fleshed out to extraordinary lengths by Michael Cummings, cartoonist for the Daily and Sunday Express, who visualised the NUM President as a puppet of the Soviet Union, threatening Britain’s democratic institutions.

Of all the cartoons published during the strike, Scargill singled out those by Cummings as causing him the greatest personal offence for the way in which he was smeared and abused. He counted 50 in the Daily Express and 34 in the Sunday edition, all intended, he said, to isolate him from union members and his leadership colleagues.

Across the trade union movement there was anger at dire anti-union bias in the coverage of most newspapers and deep frustration over the government’s success in manipulating the news agenda so that all too often broadcasters became cheerleaders for Mrs Thatcher and her campaign for a return to work.

While most trade unionists understood and even sympathised with the violent response when police confronted strikers on picket lines, they were horrified that so much of the media criticism was directed solely at the NUM and its members.

Wildly exaggerated cartoon imagery caused great offence, especially in close-knit mining communities where the miners’ wives and their supporters organised soup kitchen and food deliveries.

Why, they asked, were the pickets so often depicted as bully boys? Their thuggish demeanour was highlighted by the Daily Mail’s cartoonist mac (Stanley McMurty). In one cartoon, pickets wore hoods and carried baseball bats. Another by Cummings had strikers with clubs corralling working miners.

Why, they asked, were the pickets so often depicted as bully boys? Their thuggish demeanour was highlighted by the Daily Mail’s cartoonist mac (Stanley McMurty). In one cartoon, pickets wore hoods and carried baseball bats. Another by Cummings had strikers with clubs corralling working miners.

As the strike progressed and the police gradually gained the upper hand, a constantly recurring image deployed by cartoonists on left-wing newspapers and magazines was that of a constable cracking his truncheon down on the head of a picket.

Here was heartfelt mockery validated by the medieval scenes at the Battle of Orgreave when police on horseback charged through the massed lines of pickets.

Here was heartfelt mockery validated by the medieval scenes at the Battle of Orgreave when police on horseback charged through the massed lines of pickets.

Photographer John Harris captured the moment a mounted officer, who had his baton raised, only just missed the head of protestor Lesley Bolton – one of the iconic images regularly reproduced by the left as a reminder of police brutality.

As I leafed methodically through my vast collection of newspaper cuttings, I was struck by the absence of cartoons depicting the police charges at Orgreave.

As I leafed methodically through my vast collection of newspaper cuttings, I was struck by the absence of cartoons depicting the police charges at Orgreave.

Film of mounted police chasing the pickets is rebroadcast almost without fail when tv news bulletins and programmes revisit the strike. In the immediate aftermath of Orgreave trying to imagine a humorous slant on such barbaric scenes was perhaps a task no cartoonist could stomach or possibly seen as a step too far by newspaper editors.

Again, in my cuttings, cartoonists appeared to have been absent from action at the end of strike in March 1985.

Amid harrowing scenes of men returning to their pits, after a year’s sacrifice, without any guarantees for the future of their industry, the Conservative supporting press did not want to remind readers of the dreadful damage inflicted by Mrs Thatcher’s victory and cartoonists on the left had no wish to remind their supporters of the fallout from what had been a terrible defeat for the union movement.

The Art of Class War: Nicholas Jones, who reported the 1984-5 miners’ strike for BBC Radio, gave a lecture at Cardiff University on 21.11.2023 on how the year-long dispute was seen through the eyes of news cartoonists – their visions of heroes and villains, police brutality, working class solidarity, and the growing despair of communities starved back to work.