Devoting an entire programme to the tumultuous events in the divided mining village of Shirebrook was an inspired choice to open a season of radio and tv documentaries commemorating the 40th anniversary of the 1984-85 miners’ strike.

Devoting an entire programme to the tumultuous events in the divided mining village of Shirebrook was an inspired choice to open a season of radio and tv documentaries commemorating the 40th anniversary of the 1984-85 miners’ strike.

Flashing back and forth between past and present – seeing and hearing archive tv footage of young miners in their twenties and thirties and then listening to them again in their sixties and seventies as they relived their experiences – provided gripping reportage.

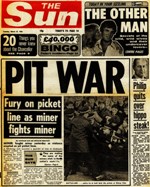

We witnessed the rage, anger and raw emotion of a village torn apart when miners on the picket line saw former friends and neighbours abandon the strike and return to work.

Swan Films’ three-part series for Channel 4 – Miners’ Strike 1984: The Battle of Britain – gave a voice to those directly involved.

They told their own story without the aid of a narrator or the “talking heads” of so-called experts; only the occasional caption kept the viewer up to date on key developments during the year-long dispute.

What unfolded at Shirebrook was in some ways exceptional. There was a back history that the documentary did not explore. Perhaps the producers thought that was a step too far when here was a chance to revisit a community which had been on the media front line of the 1984 strike, and which had its own story to tell.

A plentiful supply of archive footage brought the pit dispute back to life. An opening commentary from a reporter in a helicopter, filmed in the early weeks of the strike, set the scene.

Shirebrook, in the North Derbyshire coalfield, was described as “bandit country”, caught between Yorkshire and Nottinghamshire, a front line of a battle the National Coal Board was having with the National Union of Mineworkers and was determined to win.

From that point on the documentary relied on personal testimony from strikers, working miners, two NUM officials and an assistant chief constable.

The constant switch between images of 1984 and the reflections of now elderly men -- and the wife of one striker – was compelling, leaving the viewer in no doubt that Shirebrook had become a pivotal battleground in the North Derbyshire coalfield.

Concentrating on Shirebrook was a no brainer for Swan Films. Central Television had opened its new studio in Nottingham six months before the start of the strike and its remit was to concentrate on in-depth reporting in the East Midlands – a mission that its predecessor ATV in Birmingham had failed to fulfil.

Hence there was some amazing footage to draw on from the archive of Central TV’s numerous news reports from Shirebrook. Shots of brutal scenes on the picket line; police chasing miners through the village; then the push to get men back to work.

Film of coaches with grills on windows, protected by lines of police, racing through into the pit, illustrated the everyday violence and danger faced by those supporting the strike.

Equally powerful was archive footage of the working miner who was first through the picket line and who had an office at the pit where he could speak on the telephone to the men he assisted to return to work.

Yet more powerful testimony from the archives was supplied by Channel 4 News reporter Jane Corbin who made a name for herself with her 1984 reports and commentaries from Shirebrook which probed behind the headlines and followed the lives of the mothers and children caught up in the dispute.

Jane took the viewer back to what she had found 40 years earlier: she had been with the wives of strikers as they joined the picket line each afternoon, together with their children, some in their arms, shouting “scab” as the coaches arrived with men on the late shift.

Shirebrook had not become a flashpoint by chance. Central TV, Channel 4 News and the rest of the news media had focussed much of their coverage on the pit because the battle that developed between the strikers and working miners was one which the National Coal Board had encouraged.

North Derbyshire was chosen as the first coalfield in the country where the management intended to make a concerted effort to break the strike and the area director Ken Moses set about the task with almost military precision.

North Derbyshire was chosen as the first coalfield in the country where the management intended to make a concerted effort to break the strike and the area director Ken Moses set about the task with almost military precision.

Shirebrook was the pit where the push back began because almost half the 2,000 strong work force lived in surrounding villages rather than in Shirebrook itself.

Pit manager Bill Steel concentrated his initial efforts on making contact with those miners whose homes were furthest away from the immediate vicinity of the pit as he found the greater the distance from the mine, the less likelihood there was that miners and their families would fear intimidation.

Towards the end of June Mr Moses had written to all North Derbyshire miners offering to arrange transport for any men prepared to report for work. Each pit manager followed this up with a personal letter and then management teams began visiting miners in their home – visits that started around the Shirebrook colliery.

By the end of month 300 NUM members were back at work in the area, rising to 500 in early July.

No wonder the NUM put so much effort into the picketing at Shirebrook. According to the assistant chief constable there were often up to 5,000 strikers lined up outside the colliery, their ranks swelled by flying pickets from Yorkshire and other coalfields where the strike was solid.

Ordnance survey maps, pinned up at the offices of the board’s area headquarters, indicated the very villages and streets where the miners lived. This attention to detail paid off: North Derbyshire had a faster rate of return than any other coalfield.

Moses believed strongly in the importance of using the news media to promote the return to work – a tactic which I explored in my book, Strikes and the Media (1986) which told the story of the dispute and examined how media manipulation – almost entirely in the government’s favour – worked to Margaret Thatcher’s advantage.

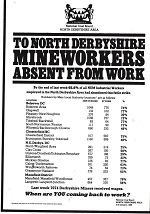

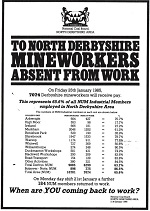

Full page advertisements appeared regularly in the Derbyshire Times listing the pits in the North Derbyshire coalfield, the number of NUM members on the books at each colliery and the number of men at work.

Full page advertisements appeared regularly in the Derbyshire Times listing the pits in the North Derbyshire coalfield, the number of NUM members on the books at each colliery and the number of men at work.

A second full-page advertisement on an opposite page listed each town and village in the area, showing the men on books and those at work for each community.

At a glance one could identify the districts and villages where men were working or on strike. The exhortation beneath the statistics – the latest figure for the number of men in receipt of wages – was abundantly clear:

“When are YOU coming back to work?”

Such was North Derbyshire’s success in leading the return to work – and by January 1985, of the 1,947 men on Shirebrook’s books, 1,533 were back at work – a Daily Telegraph reporter was invited to inspect the figures in June 1984.

“Well thumbed” pages in the colliery manager’s daily attendance record were filled up in different pens and writing styles indicating it had been filled up by local officials over a long period.

There was no positive proof that 158 men were working at Shirebrook, but the reporter said that against the entry for each man was the name of his town or village.

By early July the tactics adopted at North Derbyshire were being replicated by pit managers in the north-east of England and Scotland.

A poignant footnote to the documentary was an acknowledgement by the miner who had assisted the return to work at Shirebrook: he had paid a heavy price, lost his wife and children, and had to move away, losing lots of friends.

“Those that came out on strike I have a lot of respect for, for following their beliefs. I just want them to give me the same respect; I followed my beliefs.”

Intimidation during the strike had been hairy: his car was vandalised, his home was fitted with Home Office panic alarms, and his wife and children shadowed to and from school by a plain clothes police officer.

Footage of the demolition of Shirebrook colliery pit head in August 1994 closed the programme with the final shot showing the vast warehouse and headquarters for Sports Direct which has been built on the site.

Another timely reflection might have been a reference back to the publication in 2014 under the 30-year rule of Margaret Thatcher’s cabinet records for the period of the strike.

There are heavy redactions in her correspondence regarding her instruction that the NCB and Police needed to do more to protect those men who wanted to return to work but who were being harassed by the NUM.

There also had to be safeguards for men who were later moved to other collieries after Mrs Thatcher’s personal intervention. Lists of the names were not to be released under the 30-year rule and her papers said the names were to be kept secret for 70 to 80 years.

Judging by the hatred that was still evident in Shirebrook for those who went back to work I wondered if any of the pit’s strike breakers were given the protection stipulated by Mrs Thatcher, another example of the lasting aftermath of the strike, and perhaps one of those bitter memories that will take a generation to erase.