When reflecting on the fallout from the downfall of Peter Mandelson an all too evident faultline was the boys’ club ethos which developed among those that he worked with and their addiction to besmirching anyone perceived to have been a threat to the New Labour project.

Tony Blair failed to exercise control over the culture of toxic anonymous briefings which spiralled out of control under the malign influence of Mandelson and Alastair Campbell and became a stain on his leadership.

The departure of the last of the Blair era acolytes, Morgan McSweeney and Tim Allan – and the demise of their ennobled colleague Matthew Doyle – is an opportunity for a reset in the way Downing Street and the Labour Party brief the news media.

Perhaps the influx of women into the top jobs in the Prime Minister’s press office might be a positive step towards ending the briefing wars which have done the Labour movement so much harm.

In future those who brief on behalf of government and party should be made to adhere to a clear diktat.

Guidance on policy issues and timing often needs to be given off-the-record. Journalists do have to be advised on how to interpret and assess government decisions.

However, there is no excuse for any adviser fuelling factional infighting. Briefings to the detriment of an individual minister or MP should be banned. Any adviser caught speaking anonymously like that should face the sack.

Political journalists have had a field day since Campbell oversaw a doubling and then trebling in the number of ministerial special advisers charged with the task engineering the best possible publicity for their ministers and departments.

Labour’s SPADS, as they are known, have effectively had a free rein to adopt the macho demeanour and below-the-belt tactics championed by the Mandelson-Campbell axis.

Their misogynist briefings caused particular distress among the legions of women MPs and ministers who over recent decades have fallen foul of Downing Street or the party leadership.

For correspondents at Westminster, many of whom have excelled in their own boyo attitudes, the briefing wars have allowed and encouraged an unprecedented degree of journalistic licence.

Who knows who the “sources” might possibly be who are quoted at inordinate length, that is, if they ever existed.

Political stories based entirely on anonymous quotes are now the norm, a far cry from the standards of accuracy which applied at the start of my career.

Having reported on the birth of New Labour, and with numerous scars on my back after having come off the worse for wear after confrontations with Mandelson and then Campbell, I remain full of admiration for the sheer artistry of their character assassination.

My decade as a BBC labour and industrial correspondent meant I was damaged goods from the word go once Mandelson was taken on by Neil Kinnock.

A journalist with an affinity for the trade union movement was judged to be part of the enemy.

Mandelson was contemptuous from the start: “Once a labour correspondent, always a labour correspondent, never trust labour correspondents.”

My ability to break stories, especially those which could be considered damaging to Kinnock and then Blair, required firm rebuttal.

There was no better way than to go over my head and complain directly to BBC editors: “You do know that his shorthand note is unreliable” was one of Mandelson’s favourite ploys when encouraging the newsroom to drop one of my offending reports.

When it came to rubbishing my stories if they were being followed up by other correspondents, Mandelson’s put downs were in a league of their own.

“There is nothing in this story. It is just Nick Jones and Jeremy Corbyn at it again,” was Mandelson’s riposte to newspaper correspondents when seeking to rubbish one Saturday evening news story.

Mandelson’s menace could be intimidating. “You do realise I am having lunch with John Birt (then BBC director general) later this week.”

His readiness to go right to the top got results. After having been dispatched to interview Harriet Harman my conduct was later called into question and an apology was required.

The following Monday morning I was instructed from on high at BBC Westminster to write an immediate apology and deliver it in person.

Two days later the Daily Express had a splash exclusive that BBC had been forced to make yet another grovelling apology.

Mandelson had wilfully traded my misdeed and then taken delight in informing BBC colleagues that my punishment was well deserved.

Alastair Campbell should have the last word. From the start he treated me with contempt, accusing me of being only interested with the process of politics, obsessed with stories about spin.

An entry in The Alastair Campbell Diaries includes a telling footnote which explains why he found my exploits so irritating.

When a correspondent was needed urgently one Sunday afternoon to film a pooled interview with Blair at Chequers, I was dispatched with the crew, only to read years later of Cambell’s annoyance that the BBC had fobbed him off with that “tick Nick Jones”.

* A tick is a blood-sucking parasite

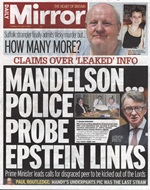

Illustrations Daily Mirror 3.2.2026; Daily Mail, 3.2.2026; I newspaper, 13.2.2026